JOSH DAVIS/BAYSIDE GAZETTE

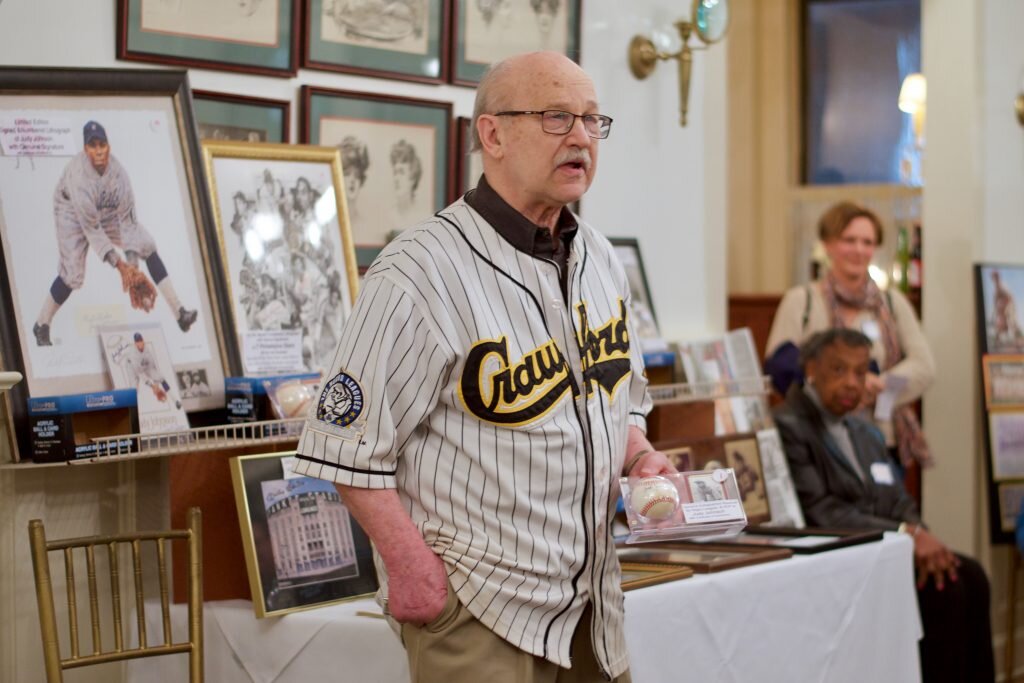

Joe Mitchell last Friday at the Atlantic Hotel in Berlin talks about his friend Judy Johnson, the late Snow Hill native who became a Negro League star and in 1975 was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

JOSH DAVIS/BAYSIDE GAZETTE

A Judy Johnson bobble head figure was among the many dozens of items available during an auction last Friday at the Atlantic Hotel in Berlin.

By Josh Davis, Associate Editor

(March 7, 2019) Judy Johnson, one of baseball’s greatest third basemen of all time, never achieved the universal reverence accorded today’s professional athletes, even though his enshrinement in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1975 reflected the respect he earned from his peers while playing in the Negro Leagues almost four decades earlier.

Now, several local and regional organizations are working to ensure that the memory of Johnson’s contributions to the game are never forgotten.

Born in 1899 in Snow Hill, Johnson played for 17 seasons in the Negro Leagues from 1921 until 1937 as a member of the Hilldale Daisies, Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, including on the 1935 Pittsburgh team considered one of the best in baseball history.

In 1954, he became one of the first African-Americans signed to a Major League Baseball coaching position when he joined the Philadelphia Athletics as an assistant coach. He died in 1989.

Dozens of Johnson artifacts were on display during a memorial fundraiser last Friday at the Atlantic Hotel in Berlin, including autographed baseballs and a worn game jersey, copies of his marriage license and death certificate. But the real highlights were the remembrances by those who knew him.

Hosted by the Worcester County Historical Society and Worcester County NAACP, the event raised money for a Johnson memorial to be installed at the Snow Hill Library.

Don Conway, a private collector of Negro League memorabilia who brought several auction items for the event, knew Johnson.

“My senior year in college, he got us tickets in Philadelphia to see the Dodgers and Philadelphia play. That’s when I saw Sandy Koufax throw his third no-hitter,” Conway said. “He used to give out college tickets to games, because he was a scout at my college and he scouted around Philadelphia.

“[Johnson] was an outstanding player and gentleman,” he continued. “He played with several teams in the Negro Leagues and he played with some famous ballplayers – he was just too young and too early to get to the next level.”

Conway said Johnson, along with his contributions to baseball, also “did all kind of kind things for people” in general.

“He was just outstanding,” he said.

Joe Mitchell, a close friend of Johnson’s, established the Judy Johnson Memorial Foundation, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to keeping his memory alive. Mitchell donated nearly 60 items for the auction last Friday and contributed $1,000 to the Snow Hill memorial.

“He played incognito and he lived incognito,” Mitchell said of his friend. “He never got any recognition at all. And today, if he knew this was happening, he would be delighted. He was very humble and very gracious.”

Mitchell, during public remarks at the fundraiser, said a team of historians evaluated the 1935 Pittsburgh Crawfords that included Johnson as the second-best baseball team of all time.

“They were only second to the 1927 New York Yankees,” he said. “Five players from that team went into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.”

Mitchell met Johnson in 1976 during a nighttime autograph session at a retail store Wilmington for former Phillies standout Bob Boone. Mitchell at the time had two sons, 7 and 10 years old, and his 10-year-old was a Little League catcher and big fan of Boone’s.

After waiting in line for more than an hour, Mitchell spotted “an elderly black gentleman” who walked up to Boone and mention something about the Phillies. Mitchell knew Johnson was a scout for the team.

“We walked over to the black gentleman after we got the ball signed by Bob Boone, and I asked him if by any chance he was Judy Johnson,” Mitchell said. “A smile grew on his face, because somebody finally recognized him.

“Here, he’d been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame the year before, supposedly one of the most famous ballplayers in the world, and nobody in that crowd of hundreds of people knew who he was,” he continued. “I was amazed at that. He was the 140th player ever inducted into the baseball hall of fame and should have been recognized by almost all of those baseball fans there – and he wasn’t.”

Mitchell later looked up Johnson in the local phone book and the two struck up a friendship.

“He came to the door the first time I knocked … and he welcomed me into his home very graciously, and we became quite close friends,” he said.

Years later, a series of unfortunate personal circumstances brought them even closer.

“I lost my wife to cancer in March of 1985 … [and] six months later I read an article where his wife of 65 years, Anita, had died. I thought, ‘he’ll be crushed,’ so I started visiting with him again,” Mitchell said. “He would sit with me in his living room and the shades were all drawn, and he cried openly. He wanted to be with Anita. He had no purpose in life any longer.”

In 1989, Johnson suffered a stroke and was put into a nursing home in Wilmington. Mitchell said his friend was paralyzed on the left side and couldn’t talk.

“One day, I walked in and he had a quizzical look on his face as though he didn’t know who I was,” he said. “And I said to him, ‘You look like you don’t recognize me.’ And he answered me and said, ‘You don’t know who I am!’ And a nurse standing by said, ‘How did you get him to talk? That’s the first words he’s said since he’s been in here.’ I said, ‘We were very close friends.’”

Mitchell established the Judy Johnson Memorial Foundation in 1996 “to educate the general public on the interesting history of the Negro League Baseball, and to keep Judy’s memory alive.”

“We try to provide an illustration of the extraordinary athletic ability of the thousands of Negro League players who played in virtual obscurity in the 60 years that they were denied the opportunity to compete in the world of organized baseball, simply because of the color of their skin,” Mitchell said.

“The white press ignored the Negro Leagues and only black newspapers covered their games,” he continued. “Many of these Negro League players, like Judy, have never been given the appropriate credit and recognition for the sacrifices they made in being denied their basic civil rights.

“Today’s Major League players who make millions of dollars each year are basically ignorant of the history of the Negro Leagues that went before them,” Mitchell said. “Some people don’t want to be reminded of segregation, but Judy told me, ‘We must be reminded so that it will never be possible for this type of injustice to be repeated.’”

Mitchell said the Negro Leagues proved that African-Americans were as good or better than their white counterparts who were allowed to play in the Major Leagues.

“Negro League Baseball is a monument to the black achievement in America,” he said, and Johnson’s talent “took him playing in a small sandlot in the streets of Wilmington, to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.”

Historical Society President Newt Weaver said he was thrilled so many people came to remember Johnson and contribute to the memorial.

“There’s a northeaster, you’ve got a foggy and cloudy night, it’s raining, it’s not too warm, and I’m just tickled to death that we’ve got some true people coming out to make a donation,” Weaver said.

“[Johnson] went through so much in his life,” Weaver said. “You’ve got to realize, he had to deal with racism and Jim Crow laws – the man couldn’t hold his head up when he walked down the street. He came from a small city like Snow Hill and moved up to Wilmington when he was a little kid, but every little child, every young man has a dream. And he caught a dream and he took it all the way to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

“That’s Judy Johnson. He never was bitter. He always had a helping hand and was a kind individual, and he was a legend. Everybody you talk to will say the same,” he added.

Weaver believes the sculpture will be educational for Snow Hill residents and visitors.

“A lot of people don’t even know he’s from Snow Hill,” he said. “When the board got together and I started mentioning this to other people, they would go, ‘Judy? Who’s she?’ They had no clue who he was and no clue he was from Snow Hill, because he moved away as a young man.

“Judy is an inspiration for anybody who has been told you can’t do this, you don’t go there, you’ll never be anything. He’s an inspiration because he strove for excellence, on and off the field.”

Additional donations to the Judy Johnson Memorial can be sent to Robert Fisher, Worcester County Historical Society Treasurer, 230 South Washington Street, Snow Hill, Maryland, 21863. For more information, call Weaver at 410-289-7215.